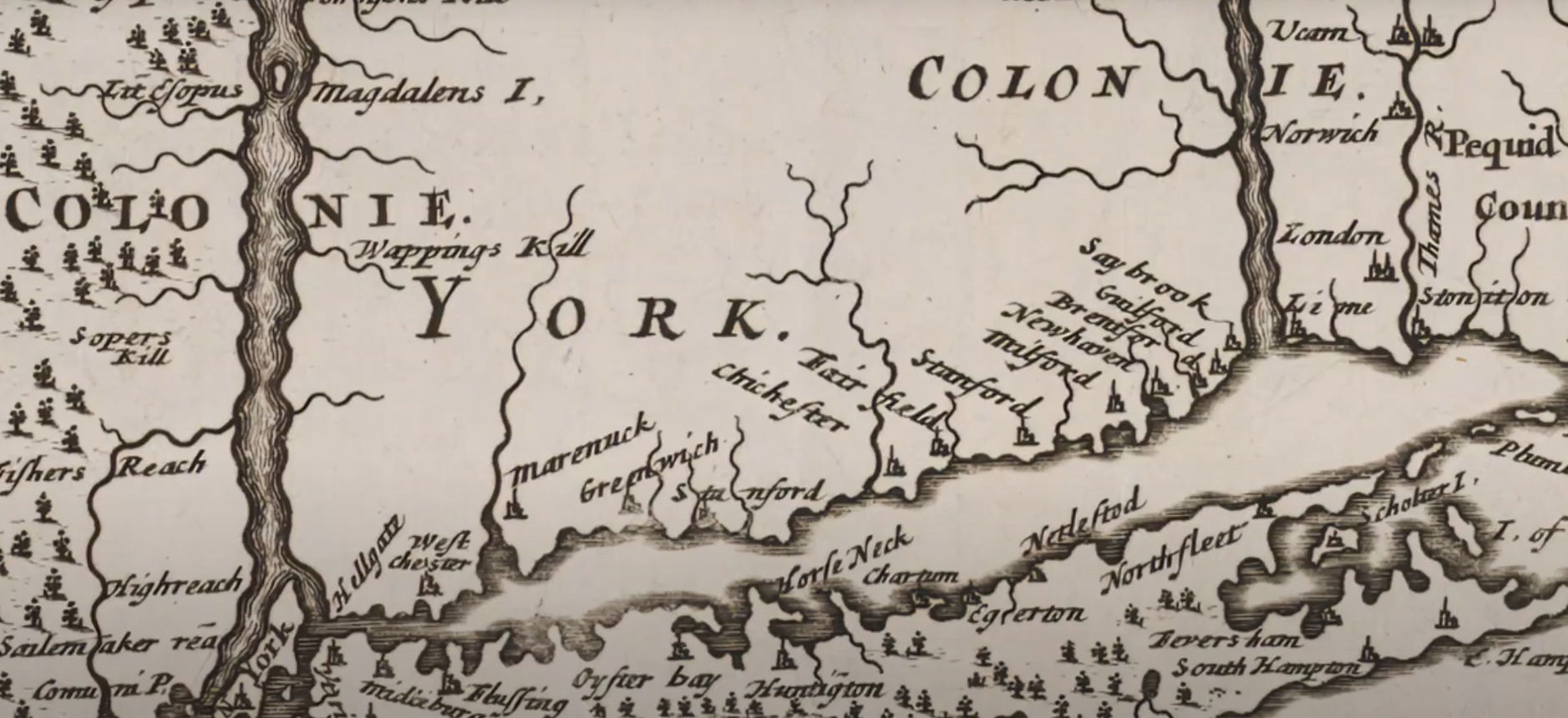

In New Amsterdam, it was common for enslaved people to be affiliated with the Dutch Reformed Church and be baptised into it. The church provided some social privileges, and baptism requirements for children also acted as a form of social control and regulation. In 1643, Reytory Angola’s name first appears in records as the witness to the baptism of Anthony, her godson. Anthony’s mother, Louise, passed away four weeks after he was born, and Reytory took charge of his upbringing. If she had not done so, Anthony’s life would have been very different.

Portret van een zwarte jonge vrouw, Rijksmuseum

One year after Anthony’s baptism, Reytory and her husband, Paulo, along with 10 other enslaved men gained partial freedom. The condition was that they paid a annual fee. Shockingly, the colonial authorities also imposed another restriction, insisting that all children of freed enslaved people remained property of the West India Company. This meant that even after his stepmother and father were freed, Anthony was forced to continue his labour. It took 17 years before Reytory was finally able to gain his freedom.

After the death of Paulo, Reytory married a freed man named Emmanuel. As they had both been freed and were partial landowners on the common land at the Bowery, they had a more advantageous legal position than most enslaved people. Reytory’s petition for Anthony’s freedom in 1661 was possible because she had adopted him legally. Reytory’s persistence and resilience pursuing her son’s freedom was one of the first successful cases of its kind, and demonstrated how enslaved people were forced to adapt in New Amsterdam.

Learn about Reytory Angola and the Dutch Reformed Church